For much of the past century, the prevailing explanation for how the earliest inhabitants reached North America seemed firmly established. Generations of students learned the same straightforward story: during the last Ice Age, when sea levels were lower, a land bridge known as Beringia connected Siberia to Alaska. Early humans, following migrating animals, crossed this landmass and eventually populated the entire Western Hemisphere.

It was a clean narrative — concise, predictable, and easy to organize into textbook diagrams and museum displays.

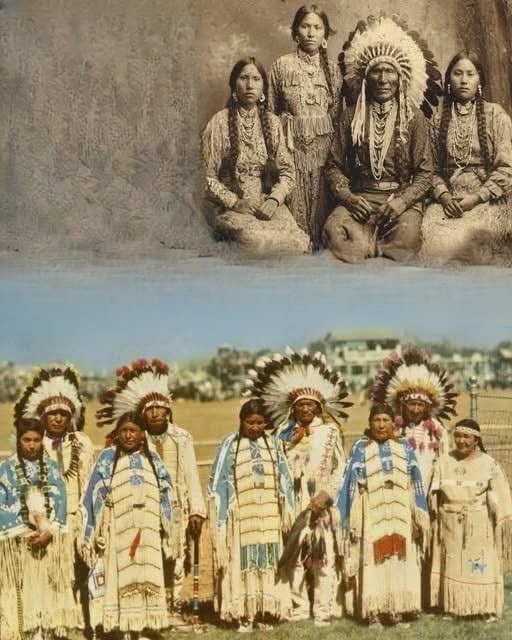

Yet history, like human movement itself, is rarely simple. Over the last decade, the rapid expansion of genetic technology has allowed researchers to study human ancestry at a level of detail once unimaginable. These scientific innovations, combined with richer partnerships between Indigenous communities and academic institutions, have opened the door to new interpretations of North America’s earliest chapters. Among the most discussed contributions are genetic studies involving members of the Cherokee Nation, an Indigenous nation with a deep cultural and historical presence in what is now the southeastern United States.

The emerging findings do not overturn existing knowledge. Instead, they deepen it. They suggest that the peopling of the Americas was not a single migration that occurred at one moment in time, but a far more complex sequence involving different groups, different routes, and potentially different eras. In many ways, the science is aligning with oral histories that Indigenous peoples have preserved for thousands of years — histories that describe long migrations, connections with earlier societies, and origins that cannot be captured by a single theory.

What follows is a closer look at how these discoveries were made, what they reveal, why they matter, and how they help reshape our understanding of the deep past.

The Traditional Story: A Single Path Through Beringia

For decades, the Bering land bridge explanation dominated scientific discussion. During the last Ice Age, massive glaciers trapped enormous amounts of water, lowering sea levels and exposing land between Asia and North America. This dry corridor served as a natural passage for humans, animals, and plant species.

Archaeologists had long believed that once these early humans arrived in Alaska, they gradually migrated southward through an ice-free corridor between two enormous glacial sheets covering much of modern Canada.

Evidence for this theory was strong:

- Stone tools discovered at early North American sites resembled those found in Siberia.

- Genetic similarities linked modern Indigenous groups to ancient populations in Northeast Asia.

- Climate models supported the existence of open migration routes during particular time windows.

For much of the 20th century, this explanation became the foundation for interpreting early American history. While alternative theories circulated — such as the possibility of coastal migrations or earlier arrivals — they were generally considered secondary.

However, as technology advanced, researchers began to see that human history was not confined to a single pathway or time period.

The Role of Modern Genetics in Reexamining Ancient Migrations

The study of ancient human movement has undergone a profound transformation thanks to genomic sequencing. Early attempts to trace population histories relied heavily on archaeological discoveries, carbon dating, and linguistic comparisons. While useful, these tools could only reveal part of the picture.

DNA analysis changed everything.

Genomic research allows scientists to observe extremely small genetic variations passed down through thousands of generations. These variations act like time-stamped markers that help researchers identify where people lived, whom they interacted with, and how they traveled across continents.

Technological advancements have made it possible to:

- Sequence ancient DNA extracted from human remains.

- Compare large datasets across global populations.

- Identify rare genetic markers that would have been impossible to detect even a decade ago.

- Distinguish between recent ancestry and extremely deep ancestral signals.

These tools have helped build a more detailed and multidimensional portrait of human migration. As more Indigenous communities choose to collaborate in this work — always with ethical standards and cultural respect — the scientific picture becomes even clearer.

The Cherokee Nation: A Rich History and a Modern Scientific Role

The Cherokee Nation is one of the most historically documented Indigenous nations in the United States. Long before European arrival, Cherokee people developed complex governance structures, sustainable agricultural systems, spiritual traditions, and extensive trade networks.

Equally important are their oral histories — stories, teachings, and ancestral knowledge passed down for generations. These narratives describe migrations, encounters with other groups, ancient homelands, and changes over vast stretches of time. They provide cultural memory that goes far beyond what archaeological layers reveal.

Importantly, Cherokee oral traditions have never fully aligned with the idea of a single migration across a land bridge. Instead, they reflect a worldview shaped by ongoing movement, diverse ancestors, and deep ties to multiple regions over long periods.

Recent genetic research involving voluntary contributions from Cherokee citizens — conducted with strict cultural safeguards and transparency — is helping to illuminate aspects of this history that written documents or archaeological finds alone cannot capture.

What the New Genetic Research Suggests

The latest studies do not dispute the foundational idea that ancient peoples entered the Americas from Northeast Asia. In fact, the majority of genetic evidence still supports this as a major source of early ancestry. What has changed is the understanding of how complex and multi-layered that process truly was.

1. Multiple Migration Waves, Not Just One

One of the most striking findings is the presence of deep ancestral markers suggesting that early populations did not arrive during a single event. Instead, several distinct waves of people appear to have reached different parts of the continent at different times.

Some genetic sequences found in Cherokee samples seem to diverge earlier than previously estimated. This suggests that early ancestors may have arrived during separate migration windows rather than all at once.

2. Possible Coastal or Marine Migration Routes

Another key insight is the detection of subtle genetic signals that appear to align with populations along the Pacific Rim. These markers are ancient — far older than any European or African ancestry introduced in recent centuries.

This supports a long-debated idea: some ancient groups may have traveled by sea or followed coastal routes along the Pacific shoreline, settling parts of the Americas long before inland glacial corridors were open. Archaeologists have uncovered early coastal settlements in places where the traditional land-route theory alone could not explain population patterns.

Genetics is now offering evidence that strengthens those findings.

3. Interactions With Diverse Groups Over Thousands of Years

Human populations rarely remain isolated. The DNA reflects subtle but detectable traces of interactions with groups who may not fit neatly into earlier models of migration. This does not mean completely separate origins; rather, it suggests that early peoples moved, met, exchanged knowledge, and sometimes intermarried over long spans of time.

These patterns align closely with Cherokee oral traditions describing:

- Exchanges with neighboring groups

- Seasonal migrations

- Movement across large geographic areas

- Ancient alliances and shared cultural practices

The convergence between oral history and science is increasingly difficult to ignore.

Supporting Indigenous Knowledge Rather Than Replacing It

One of the most meaningful aspects of this research is the way it validates Indigenous perspectives on their own origins. For generations, anthropologists tended to treat oral histories as symbolic rather than factual. Today, that view is rapidly changing.

Modern researchers now recognize that oral traditions often preserve memories of events that happened long before written documentation. While these histories may not present precise dates, they encode real experiences of migration, environmental change, and cultural evolution.

The new genetic findings do not contradict these stories — they complement them. They show that:

- Movement occurred over long periods rather than a single event.

- Early peoples interacted with multiple groups.

- Migration pathways may have included both land and water routes.

- Cultural memory carries truths that scientific tools are only now beginning to detect.

This intersection of knowledge systems is reshaping academic attitudes. Many researchers now emphasize respectful collaboration, shared authority, and community-guided research processes.

Implications for Understanding the Peopling of the Americas

If the Cherokee Nation reflects multiple migration influences, then it is likely that other Indigenous nations do as well. This means the population history of the Western Hemisphere may be far more varied and interconnected than once believed.

Key implications include:

1. The Timeline May Be Older Than Previously Estimated

Ancient markers suggest that some ancestral lines may have reached the Americas earlier than current models propose. Ongoing research may eventually refine the timeline.

2. Population Diversity Was Present Very Early

Archaeological evidence — different tool types, burial practices, and architectural styles — has long shown cultural diversity across early settlements. Genetics now provides support for the idea that these differences reflect multiple early groups rather than a single, uniform population.

3. Coastal Regions May Have Played a Larger Role

If some ancient peoples traveled by sea or along the coast, then early settlements may be buried beneath modern shorelines, submerged by rising sea levels over thousands of years. This could explain why some archaeological gaps remain.

4. Indigenous Knowledge Is Essential to Scientific Accuracy

The partnership between scientific methods and Indigenous knowledge systems is proving vital. Both contribute essential pieces of the historical puzzle.

Addressing Misinterpretations and Responsible Communication

As with any major discovery, there is potential for misunderstanding. Some people may incorrectly interpret genetic findings to support fringe theories or to dismiss established science. That is why researchers stress caution and clarity.

The Cherokee Nation has emphasized:

- Ethical sampling

- Cultural sensitivity

- Transparency about research goals

- Avoiding misrepresentation of findings

- Ensuring that data is interpreted responsibly and respectfully

Reputable scientists share these priorities. The goal is not to create speculative narratives but to refine existing knowledge with evidence-based research.

A Growing Picture, Not a Finished One

Genomic science continues to evolve. As technology improves and more Indigenous-led research initiatives move forward, the details of ancient migrations will become clearer. But one thing is already evident: the history of the Americas cannot be reduced to a single pathway or a single moment.

Instead, it is a story of movement, adaptation, innovation, and connection — repeated across millennia.

The Cherokee DNA studies offer a window into that complexity. They illustrate how old assumptions are giving way to richer, more accurate interpretations of the past. They show that scientific progress often reinforces the wisdom preserved in Indigenous communities rather than opposing it.

Conclusion: A Wider, Deeper Story of America’s Earliest Peoples

The traditional Bering Strait migration theory still holds an important place in the understanding of North America’s ancient past. But it is no longer seen as the only chapter. Modern genetics, archaeological evidence, and Indigenous knowledge together reveal a far more nuanced explanation — one that aligns with the experiences and histories of the Cherokee and many other Indigenous nations.

These discoveries invite a broader perspective:

- Human history is dynamic, not static.

- Migration is ongoing and multifaceted.

- Oral traditions carry profound historical value.

- Scientific models evolve as new information emerges.

The story of how the first peoples reached North America is richer, older, and more interconnected than once imagined. And as research continues, the picture will only grow more detailed.

Far from replacing established history, these findings expand it — offering a more complete understanding of the ancient journeys that shaped the Western Hemisphere.