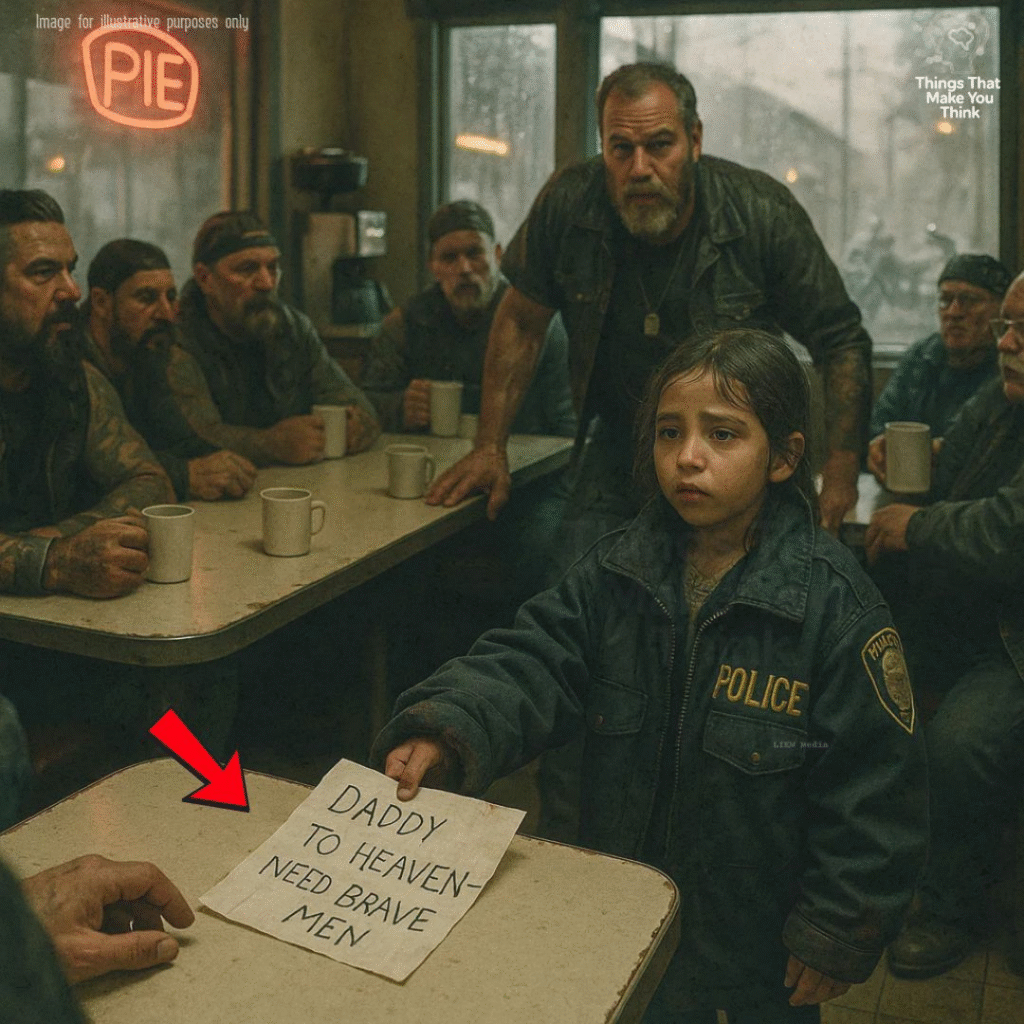

The bell over the diner door gave a tired jingle, and the room kept talking for exactly one more second—until it saw the jacket.

She was seven, maybe. The patrol jacket swallowed her to the knees, sleeves hiding her hands, the fabric heavy with rain and something darker. A brownish smear flaked along the left cuff, the kind that dries into memory. She didn’t make eye contact. She marched to our table like she’d practiced it in a mirror and slid a wrinkled paper across the chipped Formica.

“DADDY TO HEAVEN — NEED BRAVE MEN.”

Forks hovered. Coffee steam thinned. The jukebox clicked, thought better of it, and stayed quiet.

I’ve been called a lot of things—Cal “Sunday” Rourke, road captain for the Iron Wardens MC; veteran; screwup; the guy you want when a chain snaps at eighty. Nothing in those names prepared me for a kid wearing a man’s last day.

I read the note. Then I read it again, because reading is easier than feeling.

“What’s your name, kiddo?” I asked. My voice came out like I kept a mouthful of gravel.

“Lila,” she said. “Lila Ortiz.”

The name hit me like a backfire. Officer Daniel Ortiz had pulled me over two years earlier outside of town. I was riding hot, head full of ghosts. He saw the dog tag around my neck and the fatigue in my bones, and instead of a ticket he radioed for a ride, leaned on my bike, and said, “Find a way to sleep that doesn’t involve asphalt, Mr. Rourke.” He called me mister. He could’ve called me a lot worse.

“Where’s your mama, Lila?” I asked.

She pointed through the fogged window. A woman in a faded hoodie sat behind the wheel of a sedan that had seen too many winters. Her hands covered her face. Her shoulders shook, small and stubborn.

“She said I shouldn’t bother you,” Lila said. “She said this isn’t how the world works. But people at school said my daddy won’t get to heaven unless brave men walk him there.”

Someone behind me muttered a prayer. Men who never pray mutter prayers when a child speaks like that.

Boone, our president—rock of a man who could bench-press a pickup if you asked nice—lifted the note with fingers that could thread a needle. “Your daddy,” he said gently. “He was a police officer?”

“Yes.” She stood straighter. The jacket buckled around her like a parachute in wind. “He saved people.”

“What happened?” I asked before I could stop the question.

“Work,” she said. A single word, too big for her mouth. “Someone got sick. He… didn’t come home.”

I could’ve argued with fate. I could’ve argued with policy and training and all the talk shows that turn lives into points on a scoreboard. I could’ve said cops and bikers don’t mix except on the side of a highway with ticket books and bad attitudes. But the jacket was too big, and the cuff was still marked, and a seven-year-old had walked into a room full of leather and asked for help without blinking.

“Who told you brave men walk people to heaven?” Boone asked.

“My dad,” she said. “When he tucked me in.”

We paid our check. We walked her to the car. The woman—Marisol—rolled down the window slow. She looked at us with the kind of fear that doesn’t come from movies. I recognized it. It’s the fear of running out of strength.

“I told her not to bother anyone,” she said. “I’m sorry. I’m—”

“No ma’am,” Boone said, polite in a way you can’t teach. “There’s no bother here. We’ll come.”

Her eyes widened like we’d said a word she hadn’t heard in too long: yes.

The busboy had snapped a picture when Lila set the note down.

By the time I got to the shop to tune the bikes, the photo was on the internet, marching from one screen to the next, picking up comments like burrs. Half the town cried in the emojis.

Half warned the sky would fall if bikers and badges stood on the same patch of ground. A handful of loud accounts threatened to “show up and make some noise” at the funeral, as if grief were a show with an open mic.

“Don’t read the comments,” Gator said, rolling a tire with his knee. “Don’t feed the zoo.”

“I ain’t feeding it,” I grunted. “But if it throws something, I’m not letting it hit the kid.”

We ride for toys at Christmas, for vets with empty fridges, for kids with hair growing back after chemo.

We ride because the roar of a hundred engines makes you feel like the world’s heartbeat found its pace again. We also ride because promises are heavy and need horsepower.

I wrote a message in our group: “Escort for Officer Ortiz. The ask came from a daughter. Keep it clean, keep it quiet, keep it kind.”

By sundown, other clubs had chimed in.

The Gravel Saints, the Thunder Sisters out of the next county, even the church riders who wear crosses where we wear skulls.

My phone buzzed until the battery begged for mercy.

Not everyone promised peace.

A few warned we were “taking sides.” One handle I didn’t recognize wrote: “We’ll be there to film. Try something.” I set the phone facedown and changed the oil with more force than necessary.

Sergeant Hannah Price called me just after dark. We’d met on opposite ends of a traffic stop once. She was all square jaw and steady eyes, the type who writes a warning and says, “Please get that taillight fixed,” like please is part of the uniform.

“I hear your club plans to attend,” she said.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“I’m asking you to reconsider.”

“Respectfully, not happening.”

A pause. “If you do come, we’ll have to coordinate. There’s talk online.” Another pause, heavier. “Officer Ortiz was my friend.”

“We’ll keep our people in line,” I said. “We’re not there to pick a fight, Sergeant. We’re there to keep a promise that didn’t come from us.”

She didn’t answer right away. When she did, her voice had a thinner edge. “He died on a call in a motel off Exit 12. He used Narcan, performed compressions until the EMTs arrived. He…” She exhaled. “He did everything right. Sometimes everything isn’t enough.”

“I know,” I said. And I did.

“Tomorrow, 10 a.m.,” she said. “Riverside Chapel, then Hillcrest Cemetery. If the power cuts—the storm looks mean—there’s a generator, but I don’t trust it.”

“If the power cuts,” I said, looking at a row of headlamps bright enough to turn night into a suggestion, “we’ll handle it.”

Morning came like a bruise.

Clouds muscled in from the west.

The flags on Main Street went sharp and straight in the wind. I left early, the road empty enough to hear my thoughts, which I ignored. When I turned into the chapel lot, the first thing I saw was not a hearse but a river of chrome.

Bikes lined up in clean rows. Iron Wardens patches.

Gravel Saints.

Thunder Sisters’ pink lightning bolts. Christian Riders with their fish symbols. A handful of guys from clubs we used to snarl at from across parking lots without knowing why. Engines idled and coughed and killed in turn, seat by seat, like a choir learning a harmony.

Then the cruisers arrived. Blue striping. Powdered hats. Shoes shined to black mirrors. Hands near hips but not on holsters. Faces unreadable. The storm pressed low, waiting for sparks.

You could feel the old scripts trying to cue us. Us versus them. Loud versus lawful. The internet would’ve loved it. But the jacket belonged to a child now, and the cuff still remembered.

Sergeant Price stepped out of her unit and walked toward us slow, the way you walk toward a stray dog with a wounded paw. Boone met her halfway. I stood to his right. She looked up at him, then past him at the sea of bikes, then straight at me.

“Mr. Rourke,” she said.

“Sergeant.”

“Thank you for coming.”